Shocking a gem with extreme heat can shatter it. Exercising without stretching or building strength gradually can harm us.

Any real transformation, even if it appears instantaneous — even if it reads as a single recorded time after fifteen years of competitive swimming — took time and experience to emerge.

This piece asks you to descend gradually. Each section examines the same pattern at a different magnification. Take your time. The body learns best when it isn’t rushed.

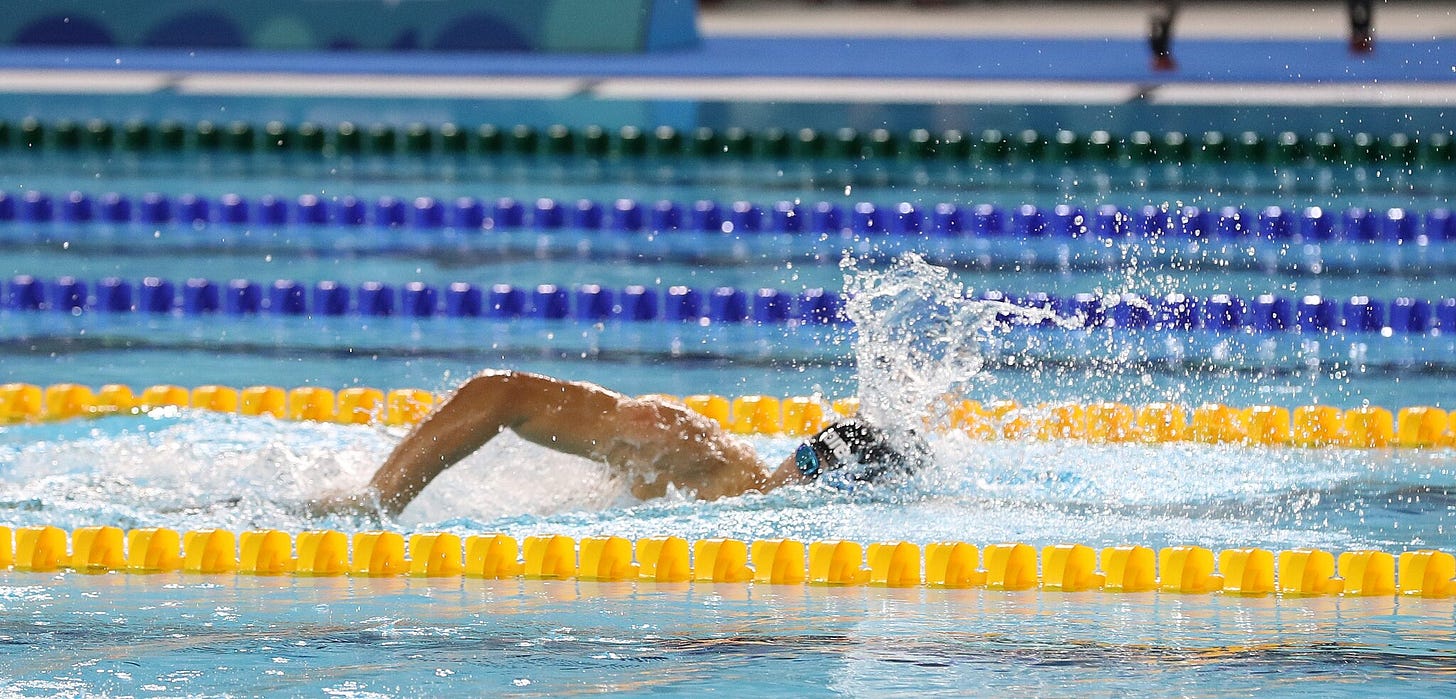

The Body in Water

I used to swim competitively in high school and into college. I was in the highest level training group offered in the area, the National Training Group. We practiced year-round, eight sessions a week. Most were two and a half hours except for the early morning hour-and-a-half sessions before school, Mondays and Wednesdays.

Yeah, it was brutal. Yeah, I wore those tiny, unforgiving Speedos. Regularly. Yes, my hair turned a strange pale straw color with a hint of neon green from being saturated in chlorinated water. And yes, I was in incredible shape, and though I wasn’t the best, I shared lanes with some who went on to the Olympics.

Have I established my credentials enough to discuss swimming? Good. I think so.

I ended up swimming primarily mid-distance for my high school team, particularly the 500-yard freestyle. Twenty lengths of the pool. Ten laps. A difficult distance — it’s not a sprint like the 100 or 200, but it’s not just endurance pace like the 1000.

For this event, they have “counters.” A person who holds a sign in the water displaying how many lengths you’ve swum, flipping the number as you approach the wall. The counter exists so the swimmer can focus on what actually matters.

Counting to twenty isn’t hard, right? Seems silly. Until you’re in the water.

Cold on impact. Painfully cold, shocking every square inch of skin. Then mercifully cool as your body temperature spikes from the effort. When you swim competitively, form is as important as endurance — more important. You count your strokes between breaths. You track each hand independently — making sure neither reaches across the midline of your chest — while keeping them coordinated with each other. Elbow high. Arm extended as far as it will go before scooping back the water to propel you forward. Meanwhile, body level with the surface. Legs straight without locking the knees, kicking from the hip with the full strength of the larger muscles. Hips rotating in timing with each forward stroke.

Every small movement. Every breath. Every exhale before the next breath. Everything registered.

There is no room for counting. Not without sacrificing the presence the body in water demands.

The counter exists because the event itself makes counting impossible. The body in water is too busy being a body in water to track a number. So we outsource the number to someone standing outside the experience.

None of this would be necessary, of course, if we were swimming for leisure, or to cross a river. The count developed for a specific, created event. And the final score? Sometimes decided by milliseconds. Recorded as a number. The victor remembered by the timer’s digits.

For example, I typed my name and “swimming” into a search bar and found an old article from the one swim meet I actually made it to in college:

Christiansen, Marchant and Tony Ness swept the top three spots in the 100-yard freestyle. Christiansen won the event in a time of 51.36. Marchant was second in a time of 52.29 and Ness was third in a time of 52.59.

52.59. That’s me.

It says nothing about the thousands of hours training. The coaches who taught us technique using their own bodies — demonstrating, then studying our movements in the water, adjusting our form with their hands on our shoulders and arms. The relationship to the water. Knowledge that can only be learned and carried from one body to another, meeting water.

It says nothing about how it felt to be me at that time. My alcoholism was budding. I was drunk nightly, stoned daily. I went on to break my wrist so badly jumping a fence while intoxicated that I needed a cast for three months and missed the rest of the season.

It says nothing about how I returned to swimming a decade later — in sobriety — and found it regulating, soothing, expansive in ways I didn’t have language for yet.

The record captured one number. How fast. Who won.

I’ve now recorded some of what surrounded that number. But what actually carries weight? The time. My name — only if the time were record-setting. My life — only if the name carries value according to whichever historians happen to be reviewing the archive, in whichever era, serving whichever power. All of it can be discarded entirely if the people who control the information decide it doesn’t matter, or decide to change what’s been recorded entirely.

Even the number that survived took fifteen years of bodies in water to produce. The record shows the millisecond. The millisecond is the culmination of the years.

The Body and the Flame

I’m an artist. My most recent creative work has been jewelry making — specifically silversmithing. I chose a patented alloy called Argentium Silver: patina resistant, hypoallergenic, more workable, and it displays a brighter white than any other metal due to the addition of Germanium. If you don’t know anything about jewelry or metals, that probably sounds like gibberish. Basically, it’s a superior silver alloy with desirable aesthetics.

When I create a new piece, I disappear into the garage for the entire day. My focus is on the metal and what it is becoming. Measuring it, cutting it, filing it. Then the heat. Annealing — bringing the metal to the precise temperature where its crystalline structure reorganizes, softening it so it can be shaped again. Under the torch, I can see the moment it happens: a faint blush moves across the surface as the atoms rearrange. Then pickling to remove stains and oxides, cleaning, applying flux to lower the melting point for smoother soldering — each step reading the metal’s response in real time. When the solder flows, it moves like water finding its level. The metal tells me what it needs if I’m paying attention. By color. By surface texture. In an instant it goes from glowing orange-red to liquid like mercury, bright white emanating heat into the air around it.

I don’t think in degrees Fahrenheit as it warms. I don’t contemplate the weight of the silver as I work. I don’t catalog every polishing wheel, burr, every supply. I don’t think about how I’ll market the piece. I’m in it, fully. A body working metal to create something beautiful.

But you know what gets recorded? Metal type. Purity. Weight. Gemstone type, cut, color, setting style, carat weight, treated or untreated. And then of course — the price.

None of the body. None of the flame. None of the metal becoming liquid, the atomic structure hardening and loosening under heat. The record keeps the numbers. The experience stays in the hands.

The Body and the New Life

OK, so arguably, these are hobbies. Swimming competitively isn’t necessary for survival. Silversmithing for jewelry is decorative work, not functional machine parts. Maybe that’s why there wasn’t a need to record more of those experiences, you might say.

I’m not going to argue. The point was never the necessity of the thing being recorded. It was the compression and loss in what does end up being recorded.

So I’ll see you and raise you the one thing none of us would be alive without: caregiving.

I haven’t carried a pregnancy, so I won’t speak to that bodily experience. I do know the experience of raising little humans. The overwhelming love of seeing a new being emerge into the world and gradually become their unique self. The terror of realizing you are responsible for the survival, development, and wellbeing of an entire human.

The tightening in my chest. The tensing in my jaw, neck, and shoulders. The feeling of a strap cinching around my head and pain in my temples when sleep-deprived, attempting to soothe a screaming infant at three in the morning. And then — the warmth and release of tension when holding your child’s warm little body, their whole weight pressed against your chest and shoulder, against your forearm. The scream softening to a whimper. The whimper giving way to breath. The breath slowing against your skin until it steadies into sleep.

That sequence — distress, attunement, regulation, rest — is the completion cycle in its purest form. A body in crisis met by a body that stays. No language required. No record made.

One night I almost couldn’t do it. I’d been awake since four-thirty. Worked a full shift. Came home to two children who’d been marinating in engineered stimulation all day — the candy that triggers craving, the videos designed to flood developing brains with dopamine. So I arrived depleted to children who were dysregulated. My son wanted to play and refused to sleep. He wouldn’t stop crying. My daughter was tired and squirming, frustrated by her brother’s loudness and wanting attention of her own. And my job, at that moment, was to be the regulating presence for two nervous systems that had been destabilized while I was away getting destabilized myself.

I stood in the hallway between their rooms and felt my whole body want to fold. The strap tightening around my head. The weight in my arms before I'd even picked anyone up. And that odd blend of guilt, grief, anger, and despair that becomes too familiar while parenting two young children in the modern world: you cannot do this. And I couldn't argue. Before I could give up entirely, my son burst out of their bedroom, and something more ancient — something like instinct — said: they need you to. So I sat on the floor between their two beds, let my son climb into my lap, gently scratched my daughter's back, and hummed. I hummed Amazing Grace. I don't normally sing or hum, and I hadn't heard that song in years. It surfaced on its own — a memory from my grandfather's funeral, when I was thirteen. For a long time, that was all I could do. Breath, sound, and presence. Eventually their breathing matched mine. Eventually the crying stopped. Eventually they slept.

There is no record of that night other than my words now. No metric captured what it cost or what it built. But something completed in that room that matters more than anything the archive holds.

You know what caregivers do record? Primarily for infants: food consumption — milk or formula. Bowel movements and urination. Fevers or concerning patterns. Body signals interpreted as data points for the health of the developing baby.

Sometimes they document special moments. But — and I can vouch for this — most of the first few years, where the most critical development occurs, is a blur. I have some pictures. Some notes. I tried to write down special moments and feelings. But most of it is unrecorded, unmeasured, unmarked.

I was too busy being present with and physically caring for another developing human to record what that development looked like or cost.

The countless hours of witness, presence, sustenance, regulation, transportation, care, clothing, shelter, love, patience, advocacy. None of it gets recorded. None of it gets compensated. And yet none of us exists without someone having done it.