When no one mirrors your outward expression accurately, or outright denies the validity of you having an experience that diverges from their own, the primary result is confusion. We can lose stability within ourselves, believing the internal experience an erroneous translation of what’s actually occurring.

If we can’t trust our own senses and perception, we are faced with a horrifying realization: we are dependent. On someone, something, anything outside ourselves that can tell us what’s real. The person who controls that mirror controls what we believe about our own experience. We don’t choose this dependency — it installs itself the moment self-trust collapses. And we will hand our perception to whoever is standing closest, whether or not they have any interest in handing it back. Naturally, we attempt to find footing outside of ourselves. Survival demands it.

Imagine seeing a group of people hiding in the bushes up the street from where you are walking. You nervously mention this to the friend you are walking with. They act confused, don’t see anyone. As you get closer you distinctly see the shape of four large men crouched, hiding behind foliage. You tell your friend you want to turn around and call for help. They laugh it off and deny anyone is there. They keep walking boldly. Teasing you to hurry up. They make it past the bush safely, so, despite feeling crazy, you decide to follow. Your entire body is tense, shoulders rounded, jaw set, barely breathing, maybe lightly sweating. You override it, it must just be you being unreasonable, crazy as your friend declares.

You get jumped, left bleeding and alone on the sidewalk.

Your friend watches, and leaves with the men, they had been part of the setup.

Let’s pause. How did that feel to read? In your body?

I know the situation sounds extreme, sounds like something we would never fall for, but most of us do fall for this, all the time.

Think of a time you felt like something was a bad idea, that you sensed you shouldn’t be doing what you were doing, but you overrode it—only to say afterward, I wish I’d listened to myself.

Now what does such an experience do to the word friend? It might just change its meaning fundamentally, it might make it hard to trust another person again.

A year later, you are walking with another friend at night. You notice something strange a block or two ahead, movement in the bushes. This time, you immediately feel threatened. You tell your friend you’d like to turn around. They don’t know about your past experience so they laugh it off. You say you’re serious. They say ok, but want to know why. You tell them you thought someone might be hiding in the bushes ahead and you want to be safe. They laugh in your face. Don’t be so silly. You say you know you might be overreacting but would feel better turning around. Repeat.

Finally, you invest in thermal vision goggles, just in case. You wear them at night. You can see people, even those hidden behind bushes and objects.

Of course you do this. You want to stay alive.

In practice, you don’t buy the goggles. You grow them. When you can’t trust those who claim to have your best interest in mind—when someone can be considerate at the dinner table and merciless in the office, splitting themselves so cleanly between settings that neither version registers the other—walking around with perception that refuses to split along with them is brutal. Compartmentalization has never been natural to me. So you learn to see. Seeing clearly is your best chance of survival when you cannot go blind.

What Actually Damages You

You know what has been the most damaging thing people have said to me? That didn’t happen. You’re making that up. Denial. Or worse: silence, stonewalling, screaming into void.

Insults? I know where you stand.

Criticism? We can communicate about that. Questions? Perfect, let’s talk.

Praise or compliment? Thank you, I’ll accept it if it lands.

Sharing your thoughts and feelings? That’s how we get to know each other.

Denial of my experience and feelings? Erasure.

Silence when I speak directly to you? Invisible.

Our sense of self requires relationship. Otherwise we cannot distinguish ourselves from anything or anyone else. We don’t know where our internal world starts and ends. We become confused. And this confusion, without returning to some type of ground or center, without an accurate relational mirror, can become chronic and infectious.

Go ahead and try to tell someone what it feels like to trip on psychedelics. It’s beyond words and our usual conscious experience. How about something simpler: try to describe to someone what happiness feels like in your body. How’s that land?

For me it’s like warm sun kissing my skin, gentle melting, tickling the fine hairs on my arm. It’s like I’m an ember emitting warmth and light, steady, real. Complete. Ready for anything, ready for more, or to just soak in sunshine, smiling with my whole body.

You might even feel it a little reading that. Now prove it’s real. With data. Go ahead. I’ll wait.

Who Holds the Proof?

Some subjective perception is harmless. Whether you like strawberry ice cream. You do or you don’t, or you like it but only if it’s Turkey Hill brand. We’ll get two pints or Neapolitan, and everyone is happy.

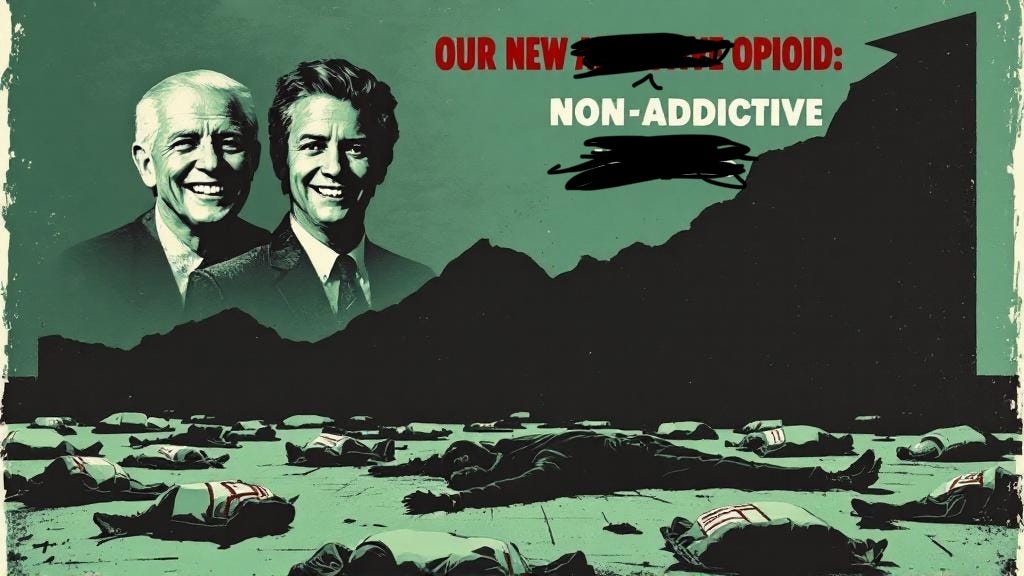

Some things are objective—they remain true regardless of whether you like them, considered their impact or not. Like a pharmaceutical company that aggressively markets a “non-addictive” opioid for everyday pain—sending sales reps to doctors with scripted lies about safety, funding fake studies, and downplaying addiction risks in internal memos while publicly insisting the drug is safe and essential for quality of life. They collect years of their own data showing skyrocketing overdose rates, addiction patterns, and deaths directly tied to their product. They already have the emails, the sales quotas, the hidden research buried in their files.

Tell me you had no intention of harming those patients, or me as a family member watching someone die slowly. Prove it.

Meanwhile, the survivor or grieving relative—body and life shattered by years of prescribed addiction—must gather medical records, overcome aggressive defense lawyers, fight statute-of-limitations barriers, and convince a courtroom the ambush was real. The company that designed the marketing blitz and hid the risks demands proof from the person bleeding on the sidewalk, proof they already documented and insured against. Every month a family spends reliving the loss to demonstrate what happened is a month the executives already priced into their legal reserves and bonus structures. Your devastation was forecasted, budgeted, and profited from.

Intent is the standard they require for proving malicious behavior. Meanwhile, they need you to prove the harm. You have to prove your experience, your loved one’s experience, is real.

They already proved it themselves. Institutions condition and produce behaviors by design and then blame you when their psychological operations cause the impact they were designed to cause.

This is the bushes all over again. The friend who walked past safely already knew what was hiding there. Purdue Pharma already had the emails admitting the addiction risks, the sales reports tracking overdose spikes, the internal data they buried while pushing more pills. They built the ambush. They have the blueprints. And the legal standard requires you—bleeding on the sidewalk—to prove someone was in the bushes.

The demand that you prove your experience is the extraction. It keeps you spending energy demonstrating what they already documented in their quarterly reports. Every hour you spend proving harm is an hour they already priced into their operating costs. Your outrage is a line item.

The Goggles

Those goggles you bought after getting jumped were the rational response to an environment that proved it would betray you. You can see what’s hiding. You can see the setup before it lands.

The question is what to do with what you see.

Most people’s instinct, once they can see the mechanism, is to explain it. Point it out. Describe in detail exactly what’s crouching in the bushes. This feels right because the body wants to complete the cycle—express what you perceive, have it mirrored, integrate, move on.

The problem: the person dismissing you already knows what’s in the bushes. Or they’re part of the setup. Your detailed explanation becomes another thing they can deny, dismiss, or stonewall. You’ve just converted their low-effort cruelty into your high-effort response.

What follows are tools.

These tools work. They also feel terrible the first time you use them, because your body has been trained to complete cycles with people who will never let them complete. Using these means accepting that some cycles close later, elsewhere, with different people. That’s the price. It’s worth it.